Sexual predators connect with potential child victims online, using a grooming process in order to establish trust with the child and, ultimately, convince the child to engage in on- or offline sexual acts. The progression of the online grooming process varies based on the goals of the predator and the feedback of the targeted child. What we know about that process is vital to the law enforcement officers tasked with identifying potential predators and acting as decoys – pretending to be minors online – to capture the predator’s attention and ultimately facilitate an arrest and conviction. However, our understanding of the nuances of the grooming process is limited by the low availability of data and research.

Sexual predators connect with potential child victims online, using a grooming process in order to establish trust with the child and, ultimately, convince the child to engage in on- or offline sexual acts. The progression of the online grooming process varies based on the goals of the predator and the feedback of the targeted child. What we know about that process is vital to the law enforcement officers tasked with identifying potential predators and acting as decoys – pretending to be minors online – to capture the predator’s attention and ultimately facilitate an arrest and conviction. However, our understanding of the nuances of the grooming process is limited by the low availability of data and research.

Enter Tatiana Ringenberg, a graduate student currently pursuing a PhD in Technology at the Purdue Polytechnic Institute. The focus of her master’s degree in computer and information technology was natural language processing, in which she studied the identification and consequences of unintended inference in text. Going into her PhD, Ringenberg wanted to identify a problem space in which she could extend her knowledge of unintended inference to how people engage in manipulation through text. After happening upon “luring communication theory” and its application to online sexual solicitation, Ringenberg knew that she had found a project where her research and expertise could help others.

“That maps so well to my research, and I would really love to help people,” said Ringenberg. “This is an area where I could start making a difference.”

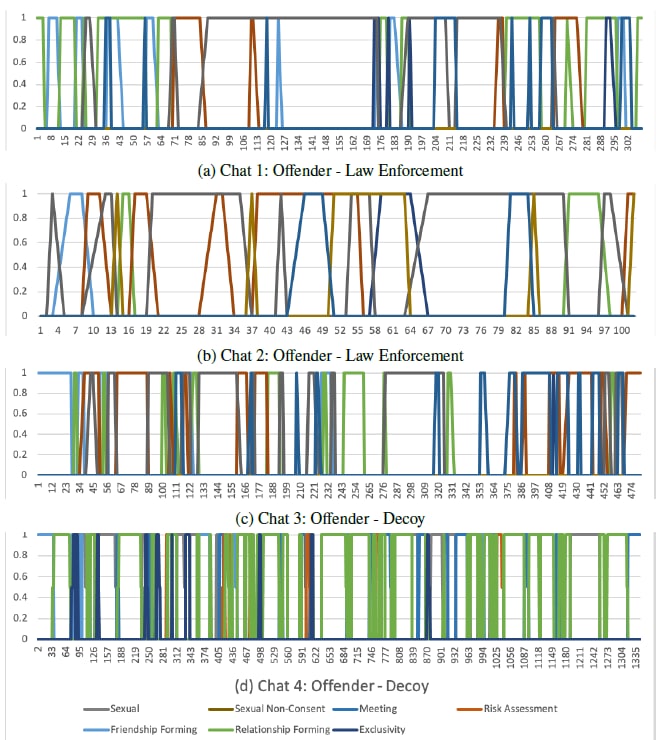

Working with faculty in the Polytechnic’s Department of Computer and Information Technology – Kathryn Seigfried-Spellar, associate professor, and Julia Rayz, professor and assistant department head – Ringenberg launched her research, “Identifying differences between decoys, victims and law enforcement in grooming conversations.” Her goal is to understand predator characteristics by studying the other participants in those conversations. She studies the online communications of children, as well as the law enforcement officers and vigilantes who pose as children, to identify and understand how they differ in their communication style, and to determine whether those differences affect how the predator communicates.

One approach to Ringenberg’s research is the study of “uncertainty language.” She applies uncertainty, a mechanism for modulating speaker commitment, to qualitatively examine how it differs between victim conversations and internet sting operations. By aligning the use of uncertain language more closely with the language of actual victims of online predators, law enforcement officers may be able to reduce the potential predator’s suspicions and be more likely to secure an arrest and conviction.

The challenge: data availability

Gaining access to transcripts of actual predator-child online conversations proved to be a significant hurdle to Ringenberg’s research. These conversations, which serve as key research data, are inherently sensitive. Transcripts must be anonymized in order to protect victims, and that process takes a significant amount of time. Past research into these conversations has typically focused on more readily available data from predator conversations with law enforcement officers or even vigilantes who pose as children online. Officers and vigilantes pretend to be children and engage with suspected online predators in an attempt to gather evidence, and these conversations are often used as research data. Ringenberg, however, knew that the research needed more accurate data.

Gaining access to transcripts of actual predator-child online conversations proved to be a significant hurdle to Ringenberg’s research. These conversations, which serve as key research data, are inherently sensitive. Transcripts must be anonymized in order to protect victims, and that process takes a significant amount of time. Past research into these conversations has typically focused on more readily available data from predator conversations with law enforcement officers or even vigilantes who pose as children online. Officers and vigilantes pretend to be children and engage with suspected online predators in an attempt to gather evidence, and these conversations are often used as research data. Ringenberg, however, knew that the research needed more accurate data.

“That data doesn’t necessarily map to the offense process, because the predator is not talking to a child, but rather an adult posing as a child,” explained Ringenberg. “From a natural language standpoint, it’s not just that there are differences in their ages and some of their characteristics; because of the differences in their development processes and their goals, we know that their communication is going to be different – the words they use, how they express themselves, what they choose to share – and I want to understand those differences.”

By studying the differences between predator interactions with children in comparison to similar interactions with law enforcement or vigilantes, Ringenberg works to understand differences in the communication that can affect the overall process.

“If we study police officer conversations,” asked Ringenberg, “are we really learning things about the predators who are talking to children, or are we only learning things about the people who talk to police officers?”

Building relationships to access better data

Ringenberg joined Seigfried-Spellar and Rayz in developing and delivering law enforcement training sessions on how to differentiate between different types of criminals – people who only want to fantasize online vs. those who want to meet and harm a child, for example – in a faster and more accurate way. These training sessions, held at law enforcement conferences, allowed the researchers to build relationships with law enforcement and ask for access to the data needed for their research.

“We told them we were having a hard time collecting data, and expressed that we would love to work with anyone who has data in this area,” explained Ringenberg. “And we had organizations reach out to us from that.”

Improved training for law enforcement

Ultimately, Ringenberg intends to use her research to create training that empowers law enforcement to do a better job posing as children in their online conversations with suspected predators. This training would also aim to help officers identify and mitigate their own biases, making their online conversations more effective. According to Ringenberg, a law enforcement officer may come off “a little bit more aggressive towards sexual topics and meetings,” because the officer is motivated to get a conviction. That aggressive approach, however, can scare off the predator – something that could be avoided with more applicable training that is founded on natural language processing.

This research also could help other researchers in psychology who use these predator-law enforcement conversations in lieu of real victim conversations.

“Studying those law enforcement conversations and thinking that they map to what the predator would say to a child – that’s incorrect,” said Ringenberg. “We want to help clear that up.”