Purdue University has a long history of racing. While the university coexists alongside Indianapolis, the home of IndyCar’s high speeds and the “racing capital of the world,” the campus attracts its own racing spectators all the same. The Purdue Grand Prix has been running since 1958 with its go-karts and philanthropic goal to raise money for student scholarships.

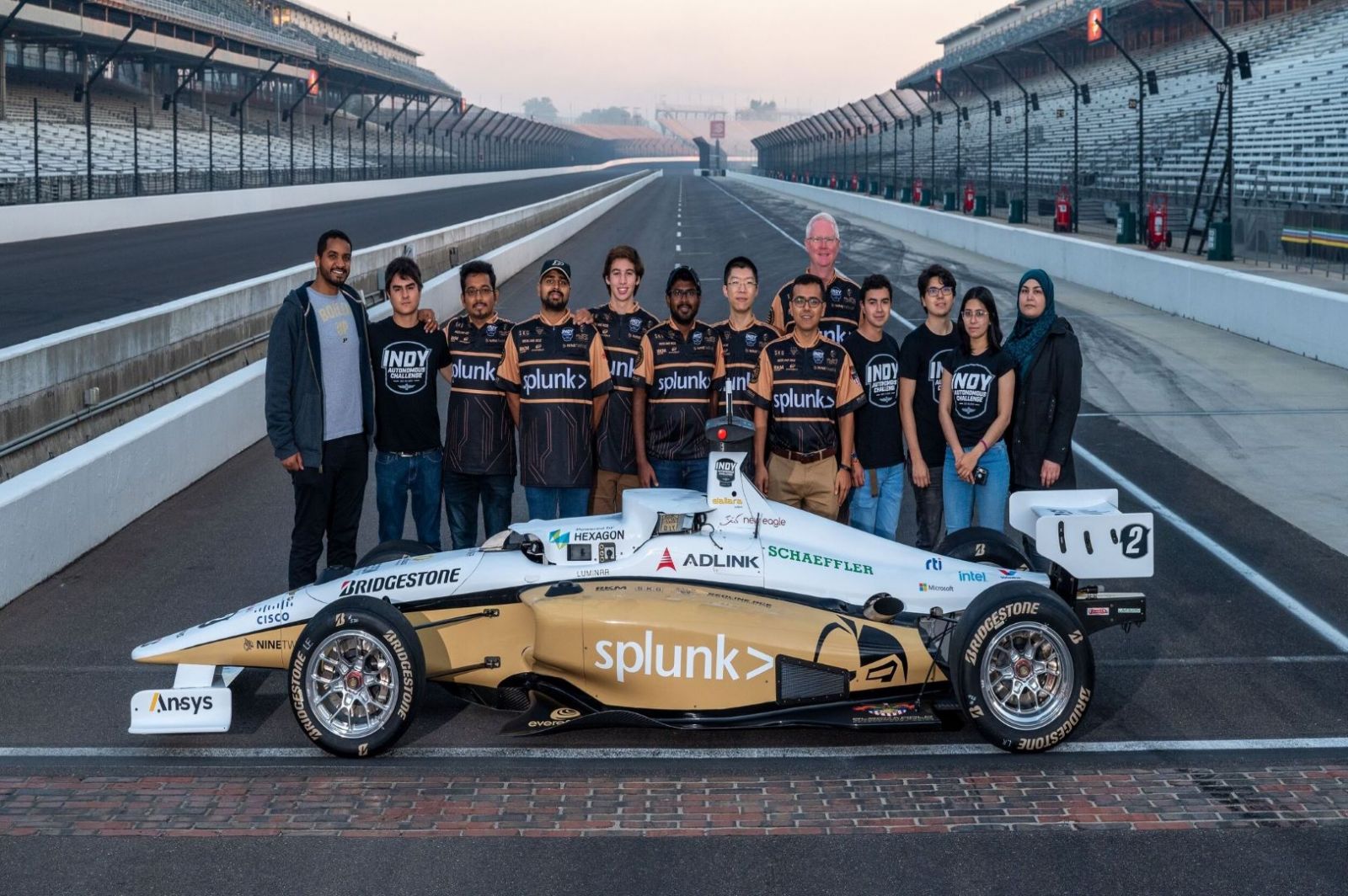

In 2021, Purdue students took their skills to a real race track for the first time at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in the Indy Autonomous Challenge (IAC). The IAC aims to advance autonomous driving technology, inspire and engage the public, and send qualified engineers and software developers into the industry.

Purdue’s Black and Gold Autonomous Racing Team competed against 20 other universities from around the world for a $1M prize. The drivers in question? None to speak of, except for a complex web of robotics and programming developed and installed in each team’s car.

This autonomous driving challenge invites STEM students to create software that performs best on a high-speed race track. It isn’t just a simulation—teams work with a real retrofitted Indy NXT car (formerly called Indy Lights), which is part of the racing series that leads up to IndyCar. That means they must push the limits of each car, with speeds reaching 200 miles per hour.

CIT students gain experience for industry jobs

Black and Gold Autonomous Racing is currently made up of Department of Computer and Information Technology (CIT) and engineering students. Purdue’s engineering students have long been involved in the Boilermaker racing tradition, but the Indy Autonomous Challenge has given CIT and engineering students the opportunity to team up in a high stakes competition.

“CIT students contribute diverse skills based on their concentration,” Manuel Mar said. Mar is a Ph.D. student in the CIT department and team member focused on controls and testing. He has also served as team lead, technical lead, and operations manager since the team was formed. “I believe CIT students specializing in networking play a crucial role in the autonomous vehicle realm, ensuring a well-rounded skill set within the team.”

The clearest real-world application of the Indy Autonomous Challenge is sending experienced candidates into the growing self-driving car industry. Shyam Kannan, a Ph.D. candidate in the CIT department and former technical team lead, is planning to take his IAC experience into industries working on autonomous vehicle technology.

“Anyone who has worked on this is going to stand out very uniquely,” Kannan said. “Problems scale exponentially with higher speeds and many people haven’t worked with platforms of this scale.”

Professors like Eric Dietz, Ph.D., also see implications for modern military challenges. Dietz, a retired Lieutenant Colonel from the U.S. Army and former senior advisor to Black and Gold Autonomous Racing, says autonomous technology can help make certain military scenarios more survivable.

“So much of the supplies that we need in our military is pretty well tethered to both our ammunition and to our logistics pipeline, which really included ammunition and fuel, principally,” Dietz said. He is also the director of both the Purdue Homeland Security Institute and Purdue Military Research Institute. “Anything we could do to help make that lifeline more secure, need less traffic, or have less people involved in it is going to actually be a more survivable military and a stronger military for the U.S.”

Dietz also noted that driverless race cars are not the end goal of the Indy Autonomous Challenge. Not only do actual racing drivers inform the development of robotics, but the personality behind the car is what engages the public.

“We’re not going to be able to put robots on the football field or on the baseball diamond,” he said. “But what if we used the robot to improve the human driver training and apply lessons from operating the robot to actually teach the drivers to drive the car fast with less training time and more safety.”

Out of testing, onto the track

In a traditional racing environment, drivers are trained over time to build the confidence needed to push the car’s limits. Black and Gold Autonomous Racing utilized an IndyCar driver from the Andretti team early in development to help them understand and program the car for these limits—like high speeds, aerodynamic forces, and traction—which caused them to think differently about the car’s robotics.

Not only do the cars need to operate at high speeds around the track, but they must also account for passing or overtaking other cars, abiding by caution or red flags, and making successful pit stops. CIT team members bring special expertise in the advanced algorithms and programming needed to operate the car safely and competitively.

While Purdue has not won the competition yet, the team is making important advancements each year toward that goal.

The January 2024 competition happened in Las Vegas at the Consumer Electronics Show, a large trade show hosted by the Consumer Technology Association. The team saw some success at last year’s competition with unprecedented speeds and stable laps during track days, Mar said, but 2024 brought difficulties to the Black and Gold team.

“During the recent Las Vegas Motor Speedway race, we faced challenges after our car collided with the wall on the fourth day,” Mar said. “Despite hitting speeds over 100 miles per hour, the team quickly addressed mechanical issues, but some drive wire system problems arose due to the impact.”

Problems aside, the experience of putting the car on the track after testing each time has been an exciting but nerve-racking accomplishment for the team.

Kannan recalled being nervous about watching a million-dollar race car driving by itself at high speeds under their programming and robotics for the first time. They had a human backup driver who could control the car remotely, but taking over at 60 miles per hour or more could be tricky if something went wrong.

“The Indianapolis Motor Speedway was pretty huge and after a few seconds, you lose sight of the car,” he said. “So you’re just looking at the screen of numbers, and it’s an intense moment, the first time. You trust code but there’s always this fear in you that a small crash could put you behind.”

“Putting the car on the track is an exhilarating experience. As a graduate student, opportunities to work on industrial vehicles are rare,” Mar said. “The development process, from proposing algorithms to testing in simulations and deploying them on the car, is an amazing educational experience.”

Mar said the future of the team is bright as they push to achieve better speeds, break records, and enhance the team’s profile. They plan to expand the team to help them continue their work in high-speed autonomous systems.

In 2024, the Indy Autonomous Challenge reports it will travel to the Monza Circuit in Italy, collaborate with the Goodwood Festival of Speed as an inaugural partner to their FOS Tech Initiative, and return to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Additional information

- Black and Gold autonomous racing at the Consumer Electronics Show, 2023 (Purdue Civil Engineering blog)

- Purdue's team page from Indy Autonomous Challenge

- CES 2024 racing recap (Indy Autonomous Challenge)